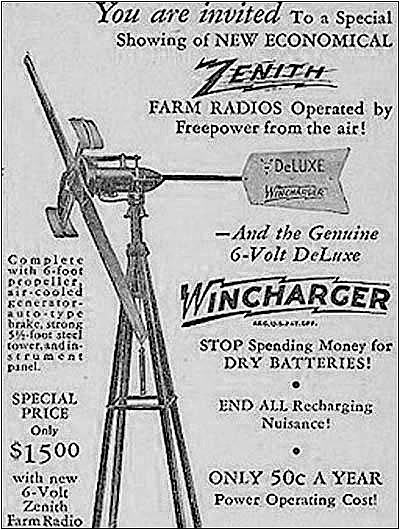

In the 1920’s and ’30’s, my grandparents farmed in Freedom Township, which is a rural area east of Emmetsburg, Iowa. According to family legend, when Charles Lindbergh flew The Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927 and landed in Paris, my grandfather set his wind generator-powered radio in front of the speaker of the party-line telephone so all their farm neighbors could listen to the news as it happened in those days before rural electrification.

I love that story because it it points out how less than a hundred years ago we lacked the basic infrastructure needed to now spend, for the first time in human existence, the majority of every waking minute of our lives engaged in consuming some form of mass communication.

In a fascinating podcast from The Food Programme on BBC Radio, Chef Magnus Nilsson makes the case that he believes the world’s most diverse baking culture can be found in the Nordic countries because the populations of those countries were so isolated and spread out that information spread very slowly. If one home cook came up with a highly individualized recipe or technique, that innovation might spread only a few miles by being handed down through the generations. Perhaps unique and highly local traditions were not bulldozered if the residents were not targeted by marketers to replace anything old with anything new?

I sometimes like to look through old community cookbooks because I hold onto the hope that I will find some lost gem of a recipe that was the unique creation of a gifted cook from the past living in a small town in the Upper Midwest of my heritage. I am usually disappointed. Most often, the recipes in community cook books are pretty universal, with only slight variations made by the individual cooks.

I recently stopped by a wonderful used book store in Mankato, Minnesota called Once Read Books and purchased the 1871-1971 Centennial Cook Book of The Albion Lutheran Church of St. James, Minnesota. It’s a terrific book and the Scandinavian section features a lot of legit Minnesota prairie recipes for Kringla, Ebelskivers, Ostkaka, and Berlinerkranser.

But a lot of the other recipes with intriguing names like Poinsettia Salad from the prolific Gladys Brekken Siem and Everlasting Salad from Tillie Frederickson turn up dozens of variations with a quick Google search.

I then made a trip to the Special Collections Department of the University of Iowa’s Main Library to reclaim a piece of family history by examining the 1934 Freedom Township Women’s Club Cook Book. While there were very few commercially prepared ingredients used in that book (the Albion Lutheran Church book published in 1971 uses scads of them like the beverage made by Gladys Brekken Siem that is made up of two parts Hawaiian Punch to one part Fresca), I found that many of the recipes, like the Lady Baltimore Cake of Mrs. Frank Goddard and the Food For The Gods of Edna High were all commonly known all across the United States.

It may be that I’m missing a larger point about community cook books, especially ones made in the prairie towns of the Upper Midwest. It may be that what drove people to record and share something central to their lives was the desire to feel connected.

There was a phenomenon known as “Prairie Madness” in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. People living in isolation on the Great Plains could fall into deep states of depression. It was a very commonly known condition and an entire genre of fiction sprang up, exemplified by Willa Cather’s “O Pioneers!” and the silent film “The Wind” starring Lillian Gish.

It may be that the authors of these community cook books wanted to record for posterity evidence that they had more connection to the world than their first-hand experience. Homemaker shows broadcast on the radio and the Ladies Home Journal were a way to experience a taste of the world beyond the kitchen window and recording your own refinements to famous recipes was a way of demonstrating that you were someone who was tuned in and participating in the zeitgeist.

Some of the recipes in the 1934 book have an international flair to them and come from parts of the world without any cultural heritage connection to the authors. While the recipes may seem off-the-mark to a modern sensibility, I think the authors had an appreciation for the world beyond their localities and wanted there to be a record that they explored the world in their own way and brought back a little treasure to their towns.

It may be that the current desire for the hyper-local in food is a reaction against being bombarded by mass media – a mass media that has been manipulated at various times by the likes of Joseph Goebbels, Mad Men, and Cambridge Analytica. Some people are craving authenticity and feel a need to put up a defense against people who poison the desire for connectivity. Maybe focusing on the local is a way of giving the finger to the Hidden Persuaders, at least in some small way? There are a lot of little zeitgeists to choose from now.

So I will continue to enjoy looking through old community cookbooks and appreciate them for what they are. I won’t be too disappointed if I never find that hidden gem from a forgotten foodie auteur. My sensibility may be different from what motivated the authors of those books.

But I am going to try making the Keokuk Pie from Mrs. C.J. Miller from the 1934 Freedom Township Women’s Club. Google didn’t turn up a thing about that one!